On Something and Nothing

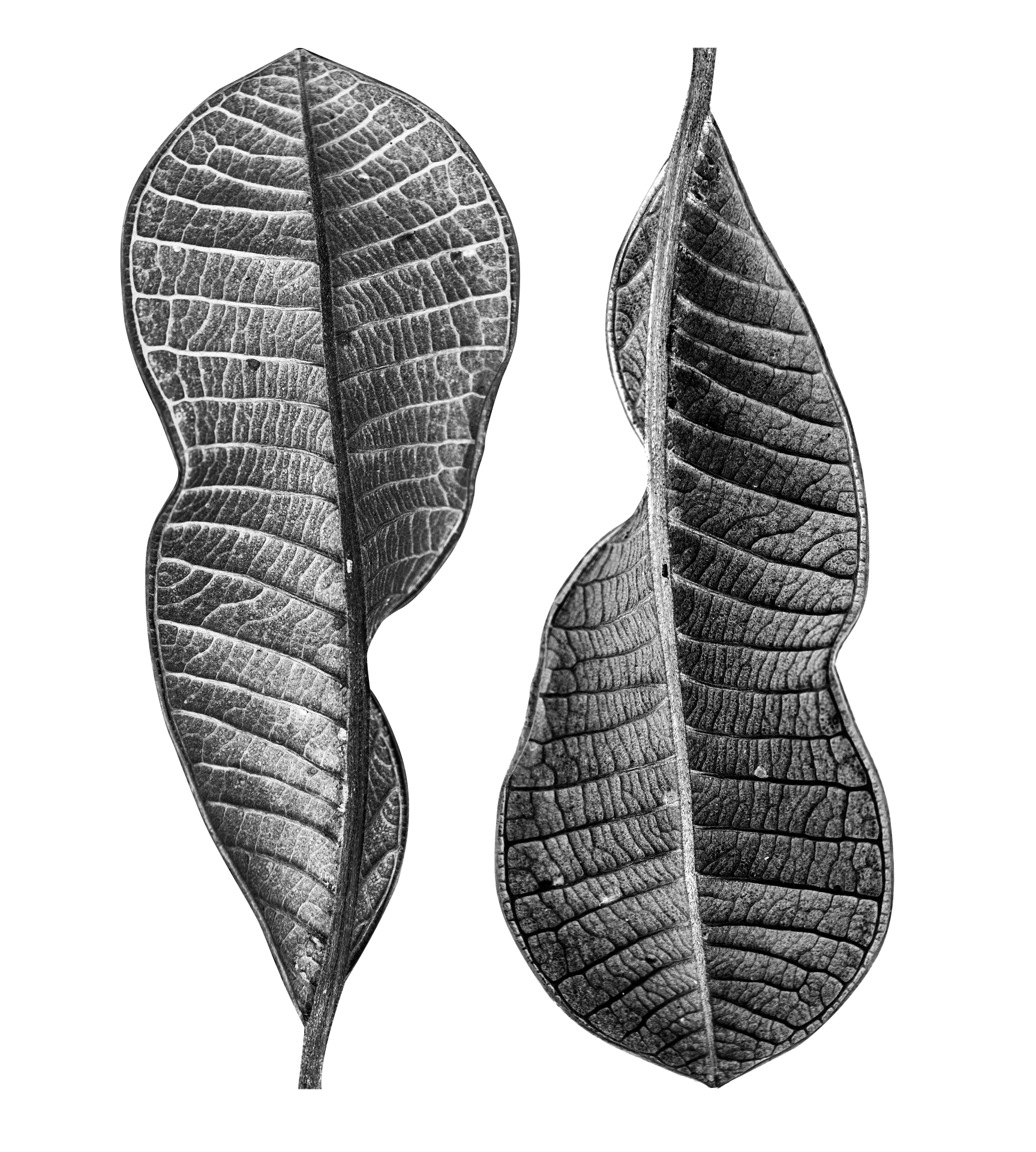

Image by Anh Nhi Đỗ Lê from Pixabay.

“To be, or not to be, that is the question” is one of the most broadly quoted lines in modern English. But is it really the question?

Pervading innumerable works of theatre, literature and music, Hamlet’s famous soliloquy speaks to a contrast at the seat of our common-sense: being and non-being.

As the most comprehensive question in philosophy and science goes: why is there something rather than nothing? However, a more pertinent question arises: what do we mean by “something” and “nothing?”

On one hand, “something” is synonymous with “anything” such that it quantifies the class of existing things.

On the other, “nothing” is used as a pronoun designating the absence of a particular thing (“There’s nothing there”); or as a predicate (“The affair meant nothing”). Though, to avoid ambiguity, philosophical “nothingness” is often replaced with “non-existence” or “non-being” – the dimension whereby existing things cease to be, or, from which they come to exist.

Because of our presupposition that existence and non-existence are separate, in philosophical discussion there arises a paradox hinting at their unity: referring to “nothing” implies a referral to something, because “nothing” itself becomes a category of thought.

To illustrate, if you hold a coin in your left hand and not in the right, you might say “there is nothing,” or “the coin is non-existent,” in the right hand. That is, for there to be non-existence, it must have the characteristic of existing as nothing for it to be so. “Nothing” is “something” by its very absence.

In fact, the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides used this reasoning to argue non-being cannot exist at all. To speak of a thing, he claimed, one has to speak of an existent thing. And since we can speak of things past, such a thing must still exist (in some sense) now, from which he concluded change was impossible. Resultantly, coming-into-being, passing-out-of-being, and non-being are also rendered untenable on this view – there’s no break between a universe that didn’t exist and one that eventually did.

Later, Aristotle concurred by proclaiming, “Nature abhors the vacuum,” albeit by separating the idea of matter and space (instead of “nothing”).

Parmenides and Aristotle make an important point. However, there’s a more subtle alternative to Hamlet’s dual ultimatum, namely the Mahayana Buddhist concept of emptiness (sunyata) situated at the core of non-dual philosophy. Encompassing this school of thought is the most profound quote from the Heart Sutra: “Form is emptiness; emptiness is form; form is not different from emptiness; emptiness is not different from form.”

Unlike our common-sense division of something and nothing, the equalising sense of form (shape, or matter) and emptiness is, perhaps, best demonstrated in the case of solid and space. If you, right now, point to “space,” your finger will inevitably, and paradoxically, direct you to what you call “something,” or solid. Likewise, if you claim to be pointing to the space between so-called solid objects by equating space with “nothing,” you’re in fact still pointing toward the objects inhering in that very space.

Equivalently, if you then point to “something,” you’ll habitually denote any object in your field of vision, but all such objects appear not just in, but as space. After all, without the background, your pointing hand itself would vanish. This conceptual bewilderment is often what causes a dog to follow your finger tip instead of the ball you’re pointing toward.

Now, since the idea of space doesn’t have a characteristic, we ordinarily categorise it as “nothing,” or non-existence. Yet, because space isn’t an entity (because it’s without a characteristic) not only is it not existent – unlike Aristotle’s claim – it’s not non-existent either; it’s not characterised, stated Buddhist philosopher Nāgārjuna, nor without character. “If there is no [independently] existent thing,” Nāgārjuna continues, “Of what will there be non-existence? Apart from existent and non-existent things, who knows existence and non-existence?”

In other words, since existence and non-existence are characteristics, neither can be said to exist independently and therefore cannot characterise any particular entity, either. [Nāgārjuna MMK reference, p.15] Just as an entity can’t be without a characteristic, solid (matter) is a function of space, and space a function of solid. You can’t get one without the other – they’re mutually dependent, like two poles of the same magnet.

Accordingly, the initial experience of emptiness is synonymous with an experience of “Oneness,” yet, Oneness itself, like the Parmenidean monist view, unwittingly takes the shape of another concept, which is only classifiable when relative to something other than what it asserts – to say everything is One is to implicitly contradict its very unity.

Echoing this point was Taoist philosopher Chuang-Tzu: “If we’re already one, can I say it? But since I’ve just said we’re one, can I not say it? The unity and my saying it make two. The two and their unity make three. Starting from here, even a clever mathematician couldn’t get it, much less an ordinary person! If going from nothing to something you get three, what about going from something to nothing? Don’t do it! Just go along with things.” [Readings reference]

Also, by declaring that existence is the only existent thing, Parmenides, in applying existence to all members of that category, offers a completely meaningless statement, just as “Everyone is unique,” simultaneously means no-one is. So when Parmenides negates non-existence he implicitly negates existence too, since, as we found, things can only be defined in relation to something other. And so the chicken-or-egg scenario of which came first is unprofitable.

But, this unitary sense of emptiness isn’t at odds with its diversity. The subtle, yet profound difference between Parmenides’ monism and non-dual emptiness is illustrated by a mirror: objects necessarily appear in it, but the mirror itself bares no characteristics – it has only the property to reflect what’s there – there’s no way a mirror looks. Yet, the reflected contents of the mirror are precisely what the mirror is: without containing any independent content, the mirror dependently contains all its content.

Importantly, this insight is non-verbal: all phenomena exist without independent nature – everything is empty; but precisely by being empty, everything is reclaimed; just as space evokes solid, and solid evokes space.

Subsequently, your only resource is to draw upon verbal concepts like “Existence” which, like a net attempting to catch water, are surprisingly ineffectual at ultimately grasping reality.

This doesn’t mean reality is an ultimately featureless blank without distinction whereby you dispense with all identification. Since form is precisely emptiness, you’re able to see through the conventions of “something” and “nothing,” or “existence” and “non-existence,” and so on, while still seeing and conceptualising all things in order to communicate.

Upon realising that something and nothing are two empty sides of the same non-conceptual reality, we might be able to tread two paths at once.

To be or not to be, therefore, isn’t the question.