The Yin-Yang of Fortune

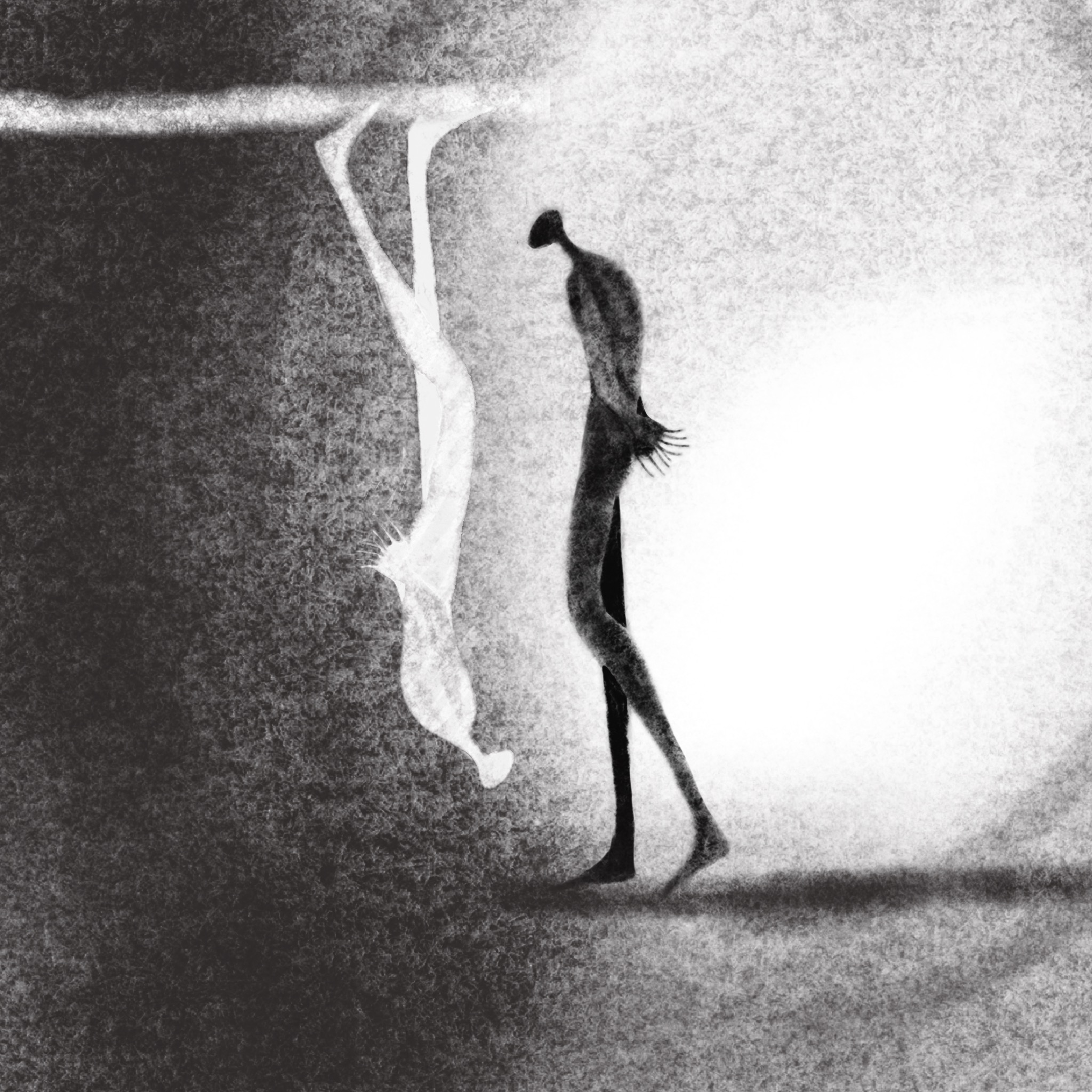

Illustration by Imy George @imysketchysketchy.

Decisions... decisions... decisions.... In other words: anxiety... anxiety... anxiety.... Did you think it over long enough? Did you consider enough factors? You worry because you attempt to account for all the variables beyond your control.

Like an insatiable gambler, you proceed to navigate life by determining each choice you make in terms of probabilistic gain or loss.

This becomes an uneasy business, since wresting upon your every choice is the ensuing consequence it inevitably brings. Contingent on your prior decision, you feel, is either success or failure, good or bad, one step forward or two steps back.

In Western moral philosophy, this was the method of utilitarianism. Jeremy Bentham, the classical initiate of the movement, declared one should apply a ‘moral arithmetic’ to every given situation, defining “right action” as that which brings about the sole intrinsic good: pleasure.

As a theory of value, he advised, we should calculate every episode of our lives so as to, like a hedonist accountant, accumulate “net pleasure” at the finish-line sum of our choices. In other words, each one of our life events contained therein can be defined as intrinsically “good” or “bad.” [1]

But can we honestly divide life into a series of episodic abstractions? Can we actually conclude whether our particular choices turn out positive or negative?

On the other hand, the I Ching or ‘Book of Changes’, the oldest of the Chinese classical texts, offers a different perspective. A book of oracles enveloping the entirety of human experience, it can be understood as a collection of wisdom evoking the fundamental principles of life to which we may accord with if we are to live harmoniously. [2]

An ancient form of divination, the text is akin to a scholarly version of fortune-telling. Though, while you wouldn’t ask the I Ching whether to bet black or red on the next spin of roulette at the casino, nor which number to pick in a playground game of origami, its premise centres on your psychological or spiritual state, and your more significant life decisions.

The book’s sixty-four hexagrams (a figure composed of six horizontal lines) are formed by combining the initial eight trigrams (three horizontal lines) circulating the yin-yang totem. To create the trigrams, orthodox Chinese ritual is to use yarrow plant stalks, spontaneously divide them, and calculate your fortune accordingly.

A less elaborate, more familiar way to achieve this is through Chinese coins. After shaking and dropping the coins, you can determine by the way they fall whether the outcome is positive: (the Yin, light, female principle) marked by an unbroken line; or negative: (the Yang, dark, male principle) signified by a broken line. This process is repeated three times until a trigram is produced.

Image source: The I Ching Gender Code.

By consulting the oracle through use of the buttons (or stalks), the eight trigrams constitute the fundamental principles integrated into every possible life situation. Any such episode of your experience is supposedly a collation of two of these principles.

In Chinese thought, the respective light and dark features of the yin-yang polarity are analogous to the light and dark side of a mountain. And since there are no mountains with merely one side, the respective oppositions are seen as intrinsic to one another. Or as the ancient Taoist Lao-tzu professed, “Recognise beauty and ugliness is born. Recognise good and evil is born.” [3]

Furthermore, the I Ching equates mountains with inner sanctity and stillness:

“Mountains standing close together – the image of keeping still. Thus the superior [person] does not permit [their] thoughts to go beyond this situation. The heart thinks constantly, this cannot be changed. But the movements of the heart [thoughts] should restrict themselves to the immediate situation. All thinking that goes beyond this makes the heart sore.” [2]

Now, you might deem this information vague. But it’s appropriate to the ambiguity of the question we would ask, such as, “What is best for me in this situation?” As it transpires, this is vague in itself.

Naturally, you might contend that flipping coins is a nonsensical format for ascertaining pressing life choices, especially the more specific kind. In the West, we're accustomed to the modern scientific method of classification and technical inquiry. So deciding our lives at the toss of a coin appears completely ludicrous because it negates any rationality whatsoever.

It neglects what we believe to be the fundamentals of decision-making: weighing pros and cons, assets and deficits, assessing probabilities, accounting for factors, or applying data. In general, meticulous speculation. Therefore, you might say, surely all this fated coins business is nothing short of superstition, bereft of any pragmatic utility to the problem at hand? Of course, this question befits our broader contemporary skepticism toward all forms of divination and fortune-telling.

However, someone of the ancient Chinese perspective may respond as follows. Firstly, how can you decide which facts involved are fixed in any given decision? For example, you’re about to complete a business deal. The facts you believed to be fixed are the state of your own company, the other company you’re working with, the market, and so on.

But all of a sudden, something you could never have considered occurs. The person you’ve successfully negotiated with falls terribly ill and can’t continue any kind of work for the foreseeable future. And so a factor you believed to be a secure component of the decision was in fact never stable in the first place.

Equivalently, in football, the manager will tactically organise their team in thorough preparation for a match. Nevertheless, most goals are scored or conceded in off-the-cuff moments nobody can hitherto account for.

In a more quotidian example, we might check a weather forecast informing us of, say, a 92% chance of rain at seven-o'clock on a given evening. But this statistic itself is constantly changing by the moment; as so often is the case, come five-o'clock the likelihood has halved.

Secondly, at which point in your choice-making process have you objectively retrieved sufficient information? Upon reflection, you might realise the endless data, causes, possibilities and permutations of the seemingly stable facts comprise a host of variables.

But the variables in any given decision are infinite. Or, as perhaps the finest interpreter of Eastern philosophy – Alan Watts – put it, this attempt equates to, “Trying to drink the Pacific Ocean with a fork.” [4]

Be honest, you mostly come to a final decision on something when you’re either tired of trying to incorporate the endless factors involved, or when you’ve spent so long deliberating, the deadline to act looms over you and the decision is made by default.

If, on the other hand, you truly believe yourself to have acquired a complete analysis of the whole situation and thus an entirely indubitable decision, it appears you've hoaxed ourselves into a false sense of affirmation.

For by cutting off the boundless flux of potentialities inherent in your choice, you've only done so arbitrarily. The ancient Chinese, at this juncture, would say this method of making a decision is just as “irrational,” or, “superstitious,” as flipping coins – because your investigation ceases in purely capricious circumstances.

The prominent allegory of this viewpoint inheres in the famous Chinese proverb “Sāi Wēng Shī Mǎ (塞翁失馬),” or “Sāi Wēng Lost His Horse.” The meaning of which is only divulged in the supplementary story of Wēng characterised as a farmer living in China’s frontier. [5]

Unsurprisingly, the most engaging Western exegesis of the parable was delivered by Watts in his lecture entitled Swimming Headless – henceforth animated by Steve Agnos and produced by the Sustainable Human project:

“Once upon a time there was a Chinese farmer whose horse ran away. That evening, all of his neighbours came around to commiserate. They said, “We are so sorry to hear your horse has run away. This is most unfortunate.” The farmer said, “Maybe.”

“The next day the horse came back bringing seven wild horses with it, and in the evening everybody came back and said, “Oh, isn’t that lucky. What a great turn of events. You now have eight horses!” The farmer again said, “Maybe.”

“The following day his son tried to break one of the horses, and while riding it, he was thrown and broke his leg. The neighbours then said, “Oh dear, that’s too bad,” and the farmer responded, “Maybe.”

“The next day the conscription officers came around to conscript people into the army, and they rejected his son because he had a broken leg. Again all the neighbours came around and said, “Isn’t that great!” Again, he said, “Maybe.”” [4]

The tale of Sāi Wēng may imply various interpretations. The positive ending entices you to read the anecdote as an image of the English idiom: “Every cloud has a silver lining.” Though, earlier in the narrative you might invoke a lesson about the implicit misfortune in any apparent stroke of luck.

However, it is the unification of this dual meaning which is paramount. It is to say the wheel of fortune never stops turning, to the extent you can never define an event as either fortunate or unfortunate. This is a sentiment again referred in the Tao te Ching: “Bad fortune rests upon good fortune. Good luck hides within bad luck. Who knows how it will end?” Lao-Tzu continues, “Therefore the Sage squares without cutting, corners without dividing...” [3]

To “corner without dividing,” exercises the Taoist philosophy of wu-wei (“effortless-action”). In this case, it is to simply navigate each singular situation on the principle it can only be treated on its present basis, as the I Ching imparts.

As a statistical analogy, you might flip a coin a hundred times and come out with, say, 86 heads and only 14 tails. You would conclude heads has a higher probability of being the result of flipping any coin. But, each specific time you flip the coin, the probability is in fact 50/50 – so venturing beyond the present situation is unprofitable. Similarly, insurance companies tell you the average life expectancy, but on any individual case, they can’t determine when it's your time to go.

Knowing this enables you to cultivate a life of liberation from the dualistic, apprehensive see-sawing of self-judgement intrinsic to every experience divided into categories of either advantage or disadvantage. In fact, Watts potently distills the entire scope of the Chinese stance in the final passage of the anecdote above:

“The whole process of nature is an integrated process of immense complexity, and it’s really impossible to tell whether anything that happens in it is good or bad — because you never know what will be the consequence of the misfortune; or, you never know what will be the consequences of good fortune.” [4]

In other words, we can’t ever prove whether any method of decision-making actually works. The objector here might mark our death as the parameter by which we measure our lives. But in the universal context offered here, the pattern of one’s life is subsumed within the whole course of events.

Moreover, regarding the specific event of one’s death, if someone made a decision deemed by others to be foolish, it would be so because it led to that person getting killed. Yet, there’s no proper way to corroborate whether the person’s demise didn’t in fact withhold them from a progressively worse circumstance, for example, making ensuing mistakes leading to the death of several others.

Conversely, someone may win the lottery and become a millionaire. Others will then say this person had an exponential bout of good fortune. But there is no absolute verification of expressing whether this doesn’t lead the person to over-indulgence and thus spill over into their social and economical downfall, and so on ad infinitum.

So, it is precisely in reaction to this principle which informs Wēng’s course of action. You’re never aptly poised to define an event as either a failure or success, since each event is simply a finite ripple of a successive chain of unknown outcomes, where each outcome is determined only by what comes next; yet, this chain endures infinitely. And so to this extent, how can “outcomes” be defined in the first place?

Now, with this in mind, we might be wise not to tip the scale as dramatically as neo-Confuncianism. That is, assume the I Ching as an exponent of an all-pervading metaphysical principle without allowing room for novelty. Maybe the intended stance the book evokes is a view of life based not so much on the causal relation between events as the pattern of events.

Ordinarily, the Western conception of causation (cause-and-effect) principally orders events as something determined by prior occurrence. This aligns with Isaac Newton’s (now outdated) scientific law concerning billiard balls, as if events were one billiard hitting another, causing the second ball to move and hit another, and so on. Likewise, in tracing the event of a particular moving billiard, we would naturally determine the antecedent billiards which had impacted upon it, thus spiraling into an infinite regression of potential causes.

Contrastingly, the Chinese never applied the I Ching’s notion of pattern as a science, but instead more to their philosophy of law. Rather than comprehending events in relation to prior causes, this perspective understands them in relation to their present pattern. In short, specific life situations are seen with regard to a fundamental view of things, instead of a linear view, as in the billiards paradigm.

It seems the traditional Western view of life has, as much as anything else, to do with grammatical convention, namely, the logical ordering of syntax (the word structure of sentences). For example, suppose someone said, “The student is bright,” and “The sky is bright.” In each case, to know what the homonym “bright” means you have to retrieve its past context. Or equivalently, you acquire the meaning in virtue of the words occurring after “bright.” Either way, you attain the meaning in a strictly linear format.

However, should you attempt an alternative mode of ordering events – say, in order of design rather than words – a strikingly different picture is presented. For example, if an illustrator initially draws two circles on a board, you naturally see two circles. If the illustrator then draws another circle around one of the initial circles to make a donut, and draws petals around the other circle to create a flower, you would, upon first seeing the board, discern a donut and a flower.

In this way, the ‘meaning’ of each figment of the drawing is relative to how you perceive it during the present moment. Of course, this is the principal notion of the I Ching: to treat every life event only with respect to how it appears in its present context. This is not to contextualise each situation as the upshot of what came before it, but to frame it in relation to what goes with it.

“Thus the idea of the I Ching,” Watts enunciates, “Is to reveal through its symbols the total pattern of the moment the question that is asked, on the supposition that the pattern of this moment governs even the tossing of the coins.” [6]

Put discursively, the point made here is the situation requiring your decision is itself contained in the endless pattern of the universal context. So, in addition to discovering the outcomes of your choices to be vague, you also discover the distinction between when a decision (a cause) and its result (an effect) is highly contentious too. Since whenever you stop to make a choice, you don’t, somehow, stand outside the pattern of events to make that choice. Your very decision is enveloped within the entire flux of the total situation.

To put it scientifically, you as an organism cannot separately navigate through your environment, nor can you be involuntarily governed by it, because you and your choices are precisely part of what you define as the so-called “external environment.” The two are intrinsic to one another. And this is exactly the signification the yin-yang provides: you can’t know one without the other.

Nonetheless, it is the linear conception of words (and thus causation) which embeds itself into the general Western idea that all phenomena are based on laws. When seeking explanations, we in the West consult a formulation of words describing such principles.

However, the Chinese refrained from such ideas regarding laws of nature. When inaugural rules began being ascribed into Chinese legislation, certain sages and scholars, including Lao-Tzu, rebuffed the decision on the premise that this would cause people to become divisive:

“Return to simplicity. Simplicity divided becomes utensils that are used by the Sage as high official. But great governing does not carve up.” The Taoist metaphor of the “uncarved block,” or “unworked wood,” (pu朴) evokes the simplicity in the natural state of humanity.

For example, in Chinese civil law, “The judge knows no written law can apply to all the complex multiplicity of circumstances that may arise,” states Watts. [6] Therefore, the judgement is based not upon what the Chinese refer to as law, but rather “justice” (I), which constitutes the first word of the I Ching.

This somewhat translates to the Western idea of equity – someone who displays a sensibility for order and reasonableness without systematically trying to cover all bases by way of stringent parameters. A person emanating ‘I’ who is capable to judge a particular circumstance as either just or unjust seems like someone we’re more inclined to trust over someone recounting their rigorous knowledge of impersonal set rules.

Herein, we arrive at one of the most important concepts of Chinese thought, namely lǐ (理), meaning “principle,” or “pattern,” regarding the order of nature. In the earliest Chinese dictionary, this word referred to the lines in a piece of jade (治玉也 zhi yu ye) or the grain in wood. The term has evolved to incorporate broad semantic ambiguity, including its verbal senses of “responding to” and “ordering.” [7]

But perhaps the most dutiful analysis of the concept is offered in Beyond Oneness and Differentiation by Brook Ziporyn:

“[Li] points to a set of concepts of “coherence” which structures these apparently opposed ideas of differentiated finiteness and undifferentiated omnipresence in a distinctive intertwining, a notion of subjectivity that also points to objectivity and vice versa.”

He adds, “So in treating jade I may sometimes cut and sometimes polish, sometimes sharpen a corner and sometimes dull an edge. “Sharpening” and “dulling” are diverse opposite operations, but they are unified, [...] as immediate phases of the total process of shaping the jade.” [7]

Akin to the yin-yang image, the examples of jade or wood convey this complexity of interrelated, co-existing events on a universal scale which occur synonymously. And since they all occur at once, the only honest way to assess the whole situation might be to understand it at a glance, in the same way we understand design at a moment’s notice. When we do this, it becomes apparent the total pattern of events can’t accurately be grasped by the systematic order of words.

A case in point is the topic of humour. You know individually what you find funny and what you don’t. But it’s impossible to choreograph a set of rules for what constitutes humour. People who have endeavoured to map the metrics of humour always reach the conclusion that if formulating an equation to consistently produce humour were possible, such equations would become sterile, and the effect would eventually cease to be funny.

Consequently the order of life, justice, or humour are things you know in yourself, but they can’t be coded into formulae. So as the I Ching suggests, the person aware of this has in themselves the receptivity for such things.

Accordingly, it seems you cannot honestly make decisions by, as Lao-Tzu noted, sorting, squaring, and dividing each eventuality into constituents. “The Way [Tao] is obscured by small completions,” remarks the other-most renowned Taoist thinker Chuang-Tzu. [8] That is, you lose sight of the whole if you abbreviate life by calling events positive or negative.

Posing a dialogue between fictional characters, Chuang-Tzu continues:

“Gaptooth said, “If you don’t know gain from loss, do perfected people know?” [...]

“Royal Relativity said, “Perfected people are spiritual. Though the low-lands burn, they are not hot. Though the He and the Han rivers freeze, they are not cold. [...]

“Master Nervous Magpie asked Master Long Desk, “I heard from my teacher, Kongzi, that the sage does not make it [their] business to attend to affairs. [The Sage] does not seek gain or avoid loss. [...]

“Master Long Desk said, [...] Ordinary people slave away, while the sage is stupid and simple, participating in ten thousand ages and unifying them in complete simplicity. The ten thousand things are as they are, and so are jumbled together.” [8]

By juggling the “ten thousand things” (the myriad objects of reference; in this case, data, facts, possibilities etc.) we harbour prolonged anxiety in confronting seemingly insurmountable problems, believing the requisite choice we make must depend on accounting for every infinitesimal piece of information.

For the ten thousand things aren't features of the world, so much as they are a feature of our inter-subjective perception of the world. This is why the art of wu-wei, instead of encountering life as a host of complicated, separate situations, is to act in accordance with the pattern of nature. On doing so, we embody Royal Relativity's advice to not get eagerly carried away by a result, nor to be too despondent in the negative.

But, if you really took into account every piece of information, you would, as Master Long Desk advises, see through the net of your classification and unify the overwhelming number of aggregates.

Because of the relative nature of fortune and misfortune, gain and loss etc., the yin-yang principle is symbolic of this inseparable opposition. When you drink you quench your thirst only to be become thirsty again, and so forth.

Noticing this, your decisions don’t require such effort, such anxiety, and appear more simplified. This, however, might seem like a distinctly over-simplified philosophy. But all things considered, the over-arching point appears to be this: if you really knew how to choose, you wouldn’t have to.

Opening an ancient poem, the third Zen patriarch Seng-ts’an declared:

“The perfect Way is

without difficulty,

Save that it avoids

picking and choosing.” [9]

This is not to bluntly condemn the act of making decisions altogether. Rather, it is to see ‘beyond,’ as it were, Bentham’s archetypal Western seeking of abstract final ends. Instead, what matters is the nature of how you feel when making decisions themselves.

It seems to choose is to hesitate before coming to a decision. It's a cognitive see-saw. So you usually doubt whether you've chosen correctly, thus unbalancing your own self-confidence. If you're aware of this lack of assurance, you begin making mistakes due to this very awareness.

But when you remember you cant ultimately define the result of any choice you make, it becomes apparent that you can't ultimately make a mistake - whatever you decide. In itself, this tends to cultivate in you a sense of self-confidence. And through this you can trust your own intuition.

Without unanimously tipping the see-saw to the side of the completely uncalculated life, the yin-yang proposes the subtle art referred to by Chuang-Tzu as someone who “harmonises people with right and wrong and rests them on [Nature's] wheel. This is called walking two roads.” [8] That is, the middle path of knowing the totality of events is irrespective of your decision to either take the Chinese point of view or not.

Because, whether or not you decide you can’t make a mistake – the eternal fortune wheel continues spinning.

Recommended sources:

[1] Bentham, J. (1780). An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation.

[2] Wilhelm, Richard. (2003). I Ching, or, Book of Changes. London: Penguin.

[3] Laozi, [trans. Stephen Addiss, and Stanley Lombardo]. (2007). Tao Te Ching. Boston: Shambhala Distributed in the U.S. by Random House.

[4] Watts, A. ‘Swimming Headless’, in Eastern Wisdom Collection: Taoism. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?...

[5] Gui Su, Qui. (2019, February 10). The Chinese Proverb of ‘Sai Weng Lost His Horse’. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/chin...

[6] Watts, A. ‘Law and Order’ in Eastern Wisdom and Modern Life. (1958-1960). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?...

[7] Ziporyn, Brook (2014). Beyond Oneness and Difference: Li and Coherence in Chinese Buddhist Thought and its Antecedents. State University of New York Press. pp.29.

[8] Ivanhoe, Philip J., and Bryan W. Norden. (2005). Readings in classical Chinese philosophy. Indianapolis: Hackett. pp.217-222.

[9] Pajin, D. (1988). On Faith in Mind – Translation and Analysis of the Hsin Hsin Ming in Journal of Oriental Studies, v.26, no.2, Hong Kong; pp.270-288. Available at: http://www.thezensite.com/ZenT...