Two Truths and a Chariot: A Buddhist Dialogue

Copyright © Saint Mary’s Press. Used by permission.

Right now you exist, as do various objects around you. But is this true?

Now, if someone questioned your individual existence, you’d customarily find this very peculiar or even degrading. Or, if I claimed there was no “me” writing this, how could I demonstrate anything but a performative contradiction?

Yet, mainstream Buddhist philosophy says otherwise. Accordingly, Siddhārtha Gautama (the Buddha) stated in his no-self theory (anatman) that the self and all things neither exist, nor don’t exist. This is, he declared, a “middle path” between views, in order to cease one’s attachment to the idea of self and therefore, psychological suffering.

Within this is the principle of the two truths: firstly, ultimate truth (paramārtha satya) corresponds to ultimately real things, that is, mind-independent objects which exist in the world regardless of our perceptual ideas; secondly, conventional truth (saṁvṛti satya), denotes objects dependent on our ideas for their existence. [1]

Understanding the two truths lies at the heart of the Milinda Pañha (“Questions of Milinda”), an ancient Buddhist dialogue between Indo-Greek King Milinda and Buddhist sage Nagasena:

Initially, Milinda asks, “Lord, what is your name?” And he’s met with a provocative reply: “Your majesty, my fellow priests address me as Nagasena; [...] it is, nevertheless, your majesty, but a way of counting, a convenient designation, a mere name, this Nagasena; for there is no ego [self] here to be found.”

“What, then,” a perplexed Milinda queries, “is this Nagasena?” The King then hurls an exhaustive set of possible answers to his own question, asking whether Nagasena is identifiable in any particular aspect of his body – namely the face, hair, nails, bones, flesh, blood, brain, lungs, liver, heart, and so forth – to which Nagasena replies “No, your majesty,” in each case.

Milinda then asks if Nagasena is any of the respective five aggregates (skandhas) in which the self can be found: physical form, sensation, perception, volition, or consciousness. Again, Nagasena replies in the negative.

He then asks if Nagasena is the sum total of all the parts listed above, or, on the other hand, whether he is something over-and-above these parts. Again, Nagasena rejects both possibilities. Triumphantly, Milinda then exclaims “Lord, although I question you very closely, I fail to discover any Nagasena. Verily, now, Nagasena is a mere empty sound. [...] Lord, you speak a falsehood, a lie: there is no Nagasena.”

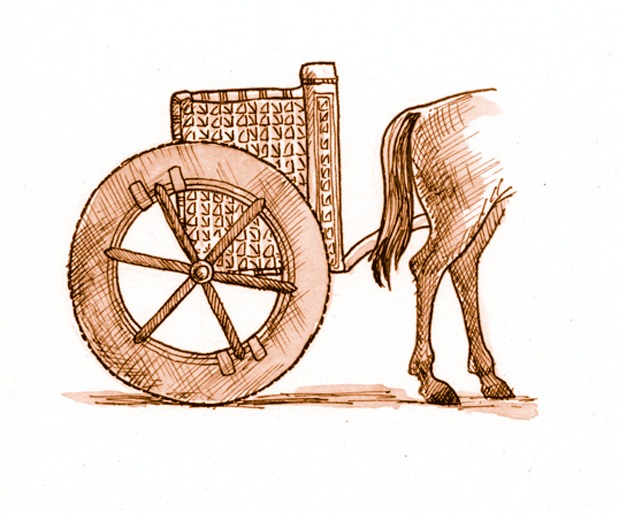

But, an astute Nagasena then retorts, “Your majesty, did you come afoot, or riding?” Milinda then admits to arriving by chariot. “Your majesty,” says a quietly confident Nagasena, “If you came in a chariot, declare to me the chariot.” Nagasena then asks if the chariot-in-itself can be found in either the pole, axle, wheels, chariot-body, banner-staff, yoke, reins, or goading-stick. “No,” replies the King.

Nagasena then asks if the chariot is all of these constituents put together; or something else over-and-above them. Again, Milinda replies “No,” to each candidate. With this, Nagasena rebuffs the King with his own reasoning, branding him a liar in front of the thousands of attendant priests. Milinda protests he has not said anything false, “I speak no lie: the word “chariot” is but a way of counting, term, a convenient designation.”

Subsequently, Nagasena’s rejoinder is to praise Milinda for this realisation and says the same point applies to the nature of the self – the components of “Nagasena” constitute a mere conventional designation for practical purposes. “But in the absolute sense,” reaffirms Nagasena, “There is no ego here to be found.” [1]

In summary, Nagasena demonstrates that when you search for the independent entity that defines what you are - or, in the example of the chariot - what any given object is, no ultimately true intrinsic property exists to which the name refers. Yet, since Nagasena and the chariot retain conventional existence, they aren’t ultimately non-existent either.

Also, because Nagasena rejects the option that he’s ultimately the sum of his parts or something distinct from them, this doesn’t relegate the term “Nagasena,” or likewise “chariot,” to a vacuous noise. Instead, nouns are useful fictions. After all, despite not being found, and therefore being only conventionally real, the chariot successfully transports Milinda from one place to another.

So, why do we have a predisposition for such fictions?

Mark Siderits asks us to suppose the parts of a chariot were arranged in the “strewn-across-the-battlefield” formation: the rim partly submerged in the mud, one spoke laying several metres from the other, and so on. In this case, we don’t have a singular name for the set. We do, however, have a term for the “assembled-chariot” formation. This reflects another difference: in the first arrangement we perceive the parts as many things; in the second arrangement we perceive them as one thing.

Why this difference? You might think it depends on proximity, but if you threw all the separate parts into a heap, you still wouldn’t identify a “chariot.” So, the change in your attitude is due to your interest in the pragmatic utility of parts arranged in a particular way. This is why Nagasena refers to words as “convenient designators.” [2]

Let’s face it, there’s only so many words you can learn before your linguistic capacity would boil over. If you had to learn a different word for the innumerably possible arrangements of parts, you’d never finish a sentence.

At this stage, you might be wondering about the parts that make up the parts, and so forth, of Nagasena or the chariot? Continuing down this line of thought, you follow an infinite regress down to subatomic particles. On the Buddha’s view, things have conventional existence simply because there are no distinct entities in the world in the ultimate sense, not even assemblies of fundamental elements (dhatus).

Interestingly, deeper than classical dhatus (water, fire, and so on), Jan Westerhoff points out that in contemporary science the most basic constituents of atoms, namely “strings,” or “quarks,” are merely theoretical posits that have never been observed in isolation. [3] For Nagasena, this is a trademark example of a useful fiction.

From his stance, the concept of fundamental particles represents a final obstacle in absolving one’s suffering: namely, clinging to the idea that there’s an ultimately true way reality is. In fact, like the Buddha, Nagasena’s seemingly negative lesson is taught as a skilful means (upaya) to deter you from the relative extremes of existence and non-existence. Therefore the middle path is, rather, a non-view – a subtle way of liberating students from all ideas about the way things are. [1]

So, if your basic assumptions about reality are based merely on interests of linguistic notation, and your words fail to denote the abundance of entities to which they refer, what should you do?

Well, orthodox Buddhist literature considers the awakened person as someone who continues to use pronouns and nouns as figures of speech, while free from the belief in the ultimately real existence of the self or things generally.

As the Pali Canon warns against, you shouldn’t mistake conventional truth as a replacement for ultimate truth. [4] Because conventional truth is itself a conventional concept which is designated by persons – whose existence is conventional to begin with. This isn’t to say you exist, or that you don’t; rather, it’s to say you’re not a separate, isolated entity – which comes to the same thing.

Therefore, since your conventional concepts are part of the world, strictly speaking, you can’t possibly stand outside them to define them; hence the Buddha’s aim to relinquish all views about reality.

In this sense, the only way to really ‘know’ so-called reality is non-verbally: to feel it and be it.

Recommended Sources:

[1] Moore, C. and Radhakrishnan, S., 1989. A Source Book in Indian Philosophy. New Jersey: Princeton Univ. Press, pp.272-292.

[2] Siderits, M., 2018. Buddhism as Philosophy. [S.l.]: Routledge.

[3] Westerhoff, J., 2009. Nāgārjuna's Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction. Oxford University Press.

[4] Giles, J., 1993. The No-Self Theory: Hume, Buddhism, and Personal Identity. Philosophy East and West, 43(2), p.175.

0 Comments Add a Comment?