What Are "You?" The Self in Buddhist Philosophy

Copyright © Saint Mary’s Press. Used by permission.

When you say “I,” what is it you’re actually referring to?

The question of where personal identity resides – or whether it exists at all – isn’t only a central philosophical question. It’s also essential to the psychological foundation of your experience, which is in fact all you have.

Some Western philosophers would say your personal identity is your physical body. Others have said it’s an immaterial soul inside the body. Some say it lies in memory, consciousness, or even one’s particular psychological continuity, as analogous to chain-mail. In Hindu thought, Vedantic philosophy conceives of the individual self (arhat) as an impersonal witness or awareness, which is inseparable from the ultimate reality (Brahman).

Alternatively, the proposal of the ‘narrative self’ suggests searching for a specific thing to define the self is the wrong question entirely. What you are, on this view, is your character - which is defined by your story. But who is telling this story? For every narrative there must be a narrator who is unidentified with the story itself.

So, what is the independent entity that defines you?

Generally speaking, the traditional presupposition of Western thought is this: the individual self (the ‘I’) exists as an intrinsic entity, distinguishable from everything else. Ordinarily, as a Westerner, you probably assume the cultural view that you indeed have personal identity.

Taking this for granted, Western dialectic has generally proceeded under the question of how a permanent self endures over time. However, similar to the rare Western heretic, Buddhist philosophy observes the more radical possibility: that there is no such ‘I’ to begin with.

Siddhārtha Gautama, known as the Buddha, taught the no-self (anatman) theory, due to the impermanence of all things (dharma). To posit the existence of a self, he declared, informs a misguided attachment to the idea of a concrete you. Like a doctor, this perspective was offered as a way to liberate oneself from the ‘I and mine’ feeling which, he claimed, is the seat of all cognitive suffering (samsara).

Initially this sounds scary, but this view of personal identity is distinctly eliminative. That is, it abolishes any such theory whereby the self is said to ultimately exist or not exist, thus constituting a middle way between extreme views, or a non-view.

On the other hand, while the West is no stranger to the no-self concept, the version offered is instead reductionist: while reducing the self from how we ordinarily perceive one another as a complex whole, it instead defines the existence of personal identity in a particular part, such as memory or a bundle of impersonal mental impressions. Understandably, this leads to ironically non-reductive theories and reinstates the idea that the self is ultimately real. [1]

So, what is the Buddha’s non-view based on? During an interview with presenter Bettany Hughes for the BBC Four’s Genius of the Ancient World series, Shantum Seth, a foremost Buddhist teacher, delivers a telling analogy of the no-self concept:

“If someone asks when you were born, you would naturally reply with a date and location. But couldn’t you also say you were born nine months before that? Yes. Weren’t you in your mother and father before that? If I took your mother out of you, you’re not Bettany anymore.”

He adds, “Bettany’s made of non-Bettany elements: the sunshine, the earth, England, and so on. And then we suddenly begin to realise there was not a single point when “Bettany” came about. So, in Buddhism it is not referred to as “creation,” but instead “manifestation.” This is not a denial that you exist, but it is denying that there is an intrinsically independent entity that constitutes the ‘I.’” [2]

In fact, the idea Seth explicates is the Buddha’s principle of dependent origination: that all things arise dependently upon their causes and conditions, to the extent which isolating the independent existence (or non-existence) of a “thing” in itself is untenable, since it’s without a definable beginning or end.

And so in the opening line of the Samyutta-nikaya, the Buddha first proposes the concept of the middle way: “That things have being constitutes one extreme of doctrine; that things have no being is the other extreme. These extremes have been avoided by the Tathagata (Gautama himself, “thus-goer”), and it is a middle doctrine he teaches.” [3]

Now, if someone questioned your individual existence, you’d customarily find this very peculiar, disarming or even down-right degrading. Or, if I claimed there was no distinct “me” writing this article, how could this demonstrate anything but a performative contradiction?

But crucially, the Buddha’s middle way envelops the principle of the two truths. What are these? Firstly, ultimate truth (paramārtha satya) corresponds to ultimately real existents. That is, mind-independent things in the world which really exist regardless of our perceptual ideas. Secondly, conventional truth (saṁvṛti satya), on the other hand denotes things which depend on our designated ideas or concepts about the world for their existence.

For example, as the fifth-century Theravada monk Buddhaghosa proclaimed in the Visuddhimagga (“The Path of Purification”):

“Just as the word “fist” is but a mode of expression for the fingers, the thumb etc., placed in a certain relation [...] when we come to examine the elements of being one by one, we discover that in the absolute sense there is no living entity there to form the basis for such figments as “I am,” or “I.”” [3]

He then gave examples of conventional entities such as an “army,” a “house,” a “tree” and myriad examples of animals. For you might ask, what happens to your “fist” when you open your hand? Or your “lap” when you stand up? Evidently, these things we perceive as real entities appear to be arbitrary linguistic conventions. And as noted, the Buddha’s notion of impermanence extends this conventional status to all things.

Despite this, there surely must be a distinct, individuated something which makes you, you? Otherwise why do we, in our common-sense, refer to “me,” “you,” “other” and so on, as they readily appear to us?

In reply to such speculation, the Buddha expounded an exhaustive list of the five aggregates (skandhas) of clinging. If the self really exists, the Buddha professed, it will be found within at least one of the five attributes: physical form (rupa), sensation (vedana), perception (samina), volition (samskara), or consciousness (vijnana).

Though, what is philosophically important is not so much the specific nature of these constituents, but the fact the self is conceptualised as a composition. It’s crucial to note the Buddhist separation of the self into components is intended to illustrate the ‘you’ cannot be found in any of the five constituents – whichever five you could possibly choose.

Despite the delineation of these characteristics, identifying the self with any particular constituent entails the difficulty that each one is impermanent. Such an identification doesn’t do justice for an essentially unchanging you. And so the Buddha only intended the five characteristics as conventional precepts. Bearing this in mind prevents inaccurately reifying the self as something else other than the aggregates. [4]

So, the question is then: once an exhaustive register of the self has been proportioned into a set number of attributes, can a permanent self be found in relation to these? To address this, we might look within ontology – the study of being and existence – there is the area of mereology: the study of the relation between parts and wholes.

For now, we are concerned only with how mereology informs personal identity. The most renowned Eastern account of this topic lies in the ancient Milinda Pañha (“Questions of Milinda”) dialogue, where the Indo-Greek King Milinda interrogates the Buddhist sage Nagasena with questions concerning the nature of the self.

Initially, Milinda asks “Lord, what is your name?” He’s met with a somewhat provocative reply: “Your majesty, my fellow priests address me as Nagasena; [...] it is, nevertheless, your majesty, but a way of counting, a convenient designation, a mere name, this Nagasena; for there is no ego [self] here to be found.”

“What, then,” a perplexed Milinda queries, “is this Nagasena?” The King then hurls an exhaustive set of possible answers to his own question, asking whether Nagasena himself is any particular aspect of the body on its own – including the face, hair, nails, bones, flesh, blood, brain, lungs, liver, heart, and so forth – to which Nagasena replies “No, your majesty,” in every case.

Milinda then asks if Nagasena is any of the respective five skandhas (bodily form, sensation, perception, volition, consciousness) and again, Nagasena replies in the negative.

He then asks if Nagasena is the sum of all the parts listed above, or whether he is something over-and-above these parts; unsurprisingly, Nagasena negates both possibilities. Triumphantly, Milinda then exclaims “Lord, although I question you very closely, I fail to discover any Nagasena. Verily, now, Nagasena is a mere empty sound. [...] Lord, you speak a falsehood, a lie: there is no Nagasena.”

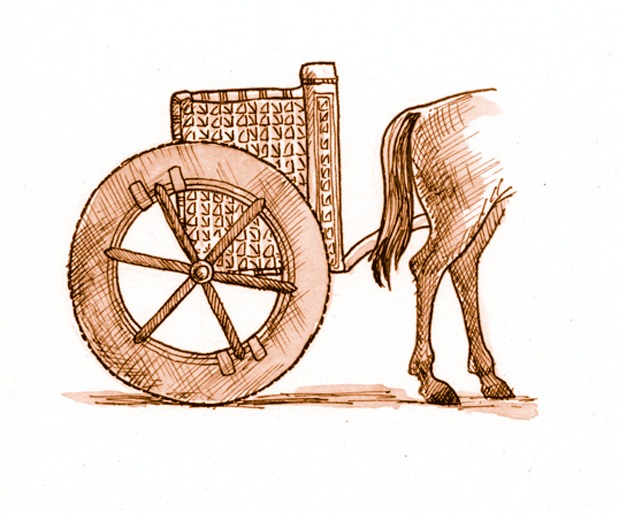

But, an astute Nagasena then retorts, “Your majesty, did you come afoot, or riding?” Milinda then admits to arriving by chariot. “Your majesty,” says a quietly confident Nagasena, “If you came in a chariot, declare to me the chariot.” Nagasena then asks if the chariot-in-itself is the pole, axle, wheels, chariot-body, banner-staff, yoke, reins, or goading-stick. “No,” replies the King.

Nagasena then asks if the chariot is all of these constituents in unison; or something else above these parts. Milinda replies “No,” to each candidate. With this Nagasena rebuffs the King with his own reasoning, branding him a liar in front of the thousands of attendant priests. Milinda protests he has not said anything false, “I speak no lie: the word “chariot” is but a way of counting, term, a convenient designation.”

Subsequently, Nagasena’s rejoinder is to praise Milinda for this realisation and points out the same goes for the nature of the self – the components of “Nagasena” constitute a mere conventional designation for practical utility. “But in the absolute sense,” reaffirms Nagasena, “There is no ego here to be found.” In other words, there is no ultimately true intrinsic ‘I’ to which the name refers. Yet, since Nagasena retains conventional existential status, he is not ultimately non-existent either. [5]

Now, as has often been the case, this passage is misinterpreted as a statement of reductionism. But the text evidently rejects this reading. As we saw earlier, the reductionist interpretation reduces Nagasena without remainder to his multiple impersonal elements (the face or heart etc.).

Though, as noted, Nagasena negates the possibility that he is either ultimately the sum of his parts or something distinct from them. Yet, this doesn’t permit us to relegate the term “Nagasena” to a vacuous noise. It’s instead a useful fiction whose proper use depends upon social agreement and context.

So, why do we have a bias for such fictions?

Mark Siderits elucidates our predisposition by asking us to suppose the parts of a chariot were arranged in the “strewn-across-the-battlefield” formation: the rim partly submerged in the mud, one spoke laying several metres from the other and so on; in this case we don’t have a singular name for the set.

We do, however, have a term for the “assembled-chariot” formation. This reflects another difference: in the first arrangement we perceive the parts as many things; in the second arrangement we perceive them to be one thing.

Why this difference? We might think it depends on proximity, but if we threw all the separate parts into a heap, we still wouldn’t say they were a single entity. No, the change in our ontological attitude, namely the fact we have a unified word for the “chariot” in the second example but not the first, is due to our interest in the pragmatic utility of parts arranged in a particular way. [5]

No doubt, this is why Nagasena calls it a convenient designator. Let’s face it; there are only so many words we can learn before our linguistic capacity would boil over. If we had to learn a different word for the innumerably possible arrangements of those parts our minds would implode. We would never finish a sentence.

So, the chariot isn’t real in an ultimately true sense because its ‘real’ existence is arbitrarily dictated by our interests of notation (or common-sense assumptions). Our common-sense ontology – our fundamental assumptions about what exists – is abundant with things we think are ultimately real, but which under analysis, are nowhere to be found.

Of course, this includes the fundamental component of experience: your idea of yourself. On the general Buddhist view, “chariot” does at least refer to something, namely a specific arrangement of parts, but it’s misleading – for it seems to be the name of a unified entity which is nowhere to be found.

At this juncture, you might be wondering about the parts that make up the parts of the chariot, and so forth? If we continue down this line of thought, we eventually follow an infinite regress all the way down to the fundamental constituents of reality, namely, subatomic particles.

Accordingly, following the Buddha’s era, the Abhidharma Buddhist tradition concluded that while, for instance, “Joe Bloggs” is in fact a conventionally real, complex whole made up of elements (dhatus), these elements (water, fire, earth, and so on) comprising this whole are themselves ultimately real.

However, for the Buddha and his later follower Nāgārjuna, although the various elements form the basis of what we define as the self, it’s not because these elements are more fundamental that we deny the existence of self, or even to outsource the self to a host of impersonal elements and merely alter the definition.

Rather, on the Buddha’s view, due to the impermanence of all things, and their existential dependence on other things, it’s simply because there are no distinct entities in the world in the ultimate sense, not even an assemblage of fundamental elements.

Interestingly, when looking at the scientific explanation for fundamental elements, the atom (from the Greek “atomos,” meaning “uncuttable”) has hence been divided into electrons, protons, neutrons and quarks.

Furthermore, Jan Westerhoff reminds us: “While the dhatus do not stray far from direct objects of experience (water, fire, and so on) the plethora of subatomic particles, quarks, or strings represent what are merely conceptual posits removed from anything empirically observable.

He continues, “Nobody will ever observe quarks, since they are theoretical posits which are inaccessible to our sensory apparatus. Principally, we notice a hint of irony surrounding the fact that our most consummate explanatory work concerning ultimately real, mind-independent existents is indeed firmly underwritten by theory-dependent human conceptualisation.” [4]

One might point out the reticence of mainstream Buddhism to subscribe to the Abhidharma theory is because it represents a final obstacle in absolving one’s suffering: namely, the idea that there is an ultimately true way things are. In short, an idea to cling to.

If you can’t identify yourself with a single aggregate, you might equate it, as some philosophers have, with some or all of the characteristics diachronically, that is, over time. For instance, you would regard yourself not as your body presently is, but as a sequence of bodies encapsulating the past and future renditions of your body.

Yet, if you include future constituents (such as your body next week) for, say, the advance train ticket you booked for your future self, this poses the problem these future constituents don’t yet exist. You couldn’t then claim your entire self-existence at this present moment.

Furthermore, on this line of thought, your candidate for a unified self is no longer. It’s rather a series of ever-changing parts. For on this account there is no consistent centre which merely shifts its ancillary properties, so this won’t suffice in determining a separate you.

Alternatively, you might defend your solid self by claiming the “You” is something distinct from the various aggregates of personhood. The self would then be defined as the owner of the body, the internal, perceiving subject we sense it to be. However, as Nāgārjuna noted, such a self couldn’t be host to these constituents, since without them, the distinct “You” would be completely unknown. Once you segregate yourself from all your constituents, there seems to be no remainder in isolation. [6]

Even on the supposition such a self could exist, on what basis it could be called a self would be tenuous, since it would be severed from all things you deem personal, such as memories, desires, or preferences, let alone its absence of a causal or temporal relation to these.

Moreover, its independence distances it further still from a conception of it being the agent who shapes your life’s decisions. Without causal connection between you and your cognitive faculties, how do you inform actions and beliefs? Such a self would be devoid of action and so can’t be assumed to have autonomy.

There are two remaining possibilities Nāgārjuna considers. Firstly, the self is something inhabiting the aggregates as a part. Or secondly, it is itself part of the aggregates. Nonetheless, both these alternatives are equally unsustainable when subjected to the arguments we articulated above. The former leads once again to a conception of a self without unity – which, by definition, couldn’t be a self. The latter entails the issue of the impermanent nature of the five aggregates, rendering the self bereft of any permanent parts.

So, if our words in fact don’t point out an entity to which they refer, what are we to do?

In response to this issue, Buddhist literature permits the concept of the self or ‘I’ to which we denote is wholly compliant with personal pronouns such as “I,” or “me,” in everyday matters – provided we’re aware these self-references do not actually refer to any independent entity in the ultimately true sense.

This point is perhaps best illuminated in the Diamond Sutra, where in dialogue with the Buddha, the monk Subhuti says to another:

“When the Tathagata [the Buddha] speaks of a view of a self, the Tathagata speaks of it as no view. Thus is it called ‘a view of the self.’”

The Buddha then follows, “See, and believe all dharmas but know, see, and believe them without being attached to the perception of a dharma. And why not? The perception of a dharma, Subhuti, the ‘perception of a dharma’ is said by the Tathagata to be no perception. Thus it is called the ‘perception of a dharma.’” [7]

It seems, then, use of first-person pronouns is entirely necessary for basic communication, despite a failure to ultimately refer to anything. Resultantly, the no-self theory means we needn’t panic and radically overhaul of our language.

Orthodox Buddhist thought considers the awakened person as someone liberated from the belief in the ultimately real existence of the “You” referred to in speech, while maintaining awareness of its conventional, dependent existence.

Conversely, on this account, identification with the existence of an independent, separate self offsets the accompanying psychological problems of a self-image which is then susceptible to being fragmented, hurt, desirous, jealous, violent, and so on.

Fundamentally, the no-self idea may strike you as unsettling, profusely negative or defamatory. But the common misinterpretation concludes the Buddha’s theory as an assertion of the ultimate non-existence of the self.

For as Siderits points out, the “no-self” title is not to be taken literally. Rather, the Buddha merely taught this negative extreme as a skilful means (upaya) to initially deter contemporary schools of thought from the opposite extreme: the view that the separate self exists. [5]

As the Pali Canon warns against, we shouldn’t conflate the conventional truth as a replacement for the ultimate truth. Because conventional truth is itself a conventional concept which is designated by persons – who’s being is conventional and dependent in the first place.

This harmonious inseparability between self and world is, through opposite means, similar to the abovementioned Vedantic view. Though, unlike the Hindu stance, Buddhism doesn’t ultimately declare the positive existence of self.

Finally, in a telling anecdote, the Buddha was asked whether the self exists after death; does not exist after death; both exists and does not exist after death; or neither exists nor does not exist after death – to which he replied “No,” to each.

The point of these negations does not intend to signify that the self exists, yet, it transcends conceptualisation.

Instead, it articulates that any concept regarding a self is inconceivable – but the Buddha even rejected this idea too. [3]

Recommended Sources:

[1] Giles, J., 1993. The No-Self Theory: Hume, Buddhism, and Personal Identity. Philosophy East and West, 43(2), p.175.

[2] BBC Four. Genius Of The Ancient World: Buddha. 2015. [film].

[3] Moore, C. and Radhakrishnan, S., 1989. A Source Book in Indian Philosophy. New Jersey: Princeton Univ. Press, pp.272-292.

[4] Westerhoff, J., 2009. Nāgārjuna's Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction. Oxford University Press.

[5] Siderits, M., 2018. Buddhism as Philosophy. [S.l.]: Routledge.

[6] Garfield, J., 1995. The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way: Nāgārjuna's Mulamadhyamakakarika. New York: Oxford University Press.

[7] (trans.) Red Pine, 2002. The Diamond Sutra: The Perfection Of Wisdom. [online] Terebess.hu. Available at: https://terebess.hu/zen/mester...

0 Comments Add a Comment?